12 Apr A brief history of Collecting

A brief history of Collecting

Collecting is the process through which objects are organized, categorized, stored, admired, understood and appreciated in a distinct and systematic manner, driven by the idea of composing a wider Whole determined by its fragments. A collection seems nothing more than a completed self-sufficient entity consisting of a specific sum of smaller individuals, capable of maintaining its entirety whilst opening itself up to a plethora of inner parts. The question that arises, once one starts considering the concept and framework of Collecting, is associated with the way it occurs, as well as the criteria according to which it comes to life. To put it bluntly: Why collect? And what to collect?

One of the first associations that come to mind regarding the definitions and conceptualization of collecting is a child’s very first relationship with his toys. Favorites or not, whether worn out or brand new, they are charged with an almost cult value and end up becoming an integral part of a child’s life. The criteria of collection in this case could hardly be restraint in a functionalistic understanding of simply hoarding as many toys as possible due to the fact that they have a specific use. The toy transcends in the eyes of the child its mere materialistic restrictions and becomes a medium towards fantasy. It’s the bear that took strolls with you up on that rainbow, the fastest car that helped you win that race on the moon that one time, or even your bestest (sic) friend in the entire wide world, made solely out of plastic and cheap fabric, with whom you’ll share all your secrets. Evidently that kind of a collection draws its value from a deep emotional involvement, rather than any other kind of market driven rating that might guaranty a profit in the stock market.

But children grow old, and go on the venture in many other kinds of collecting practices, even in the tender yet oh so revolutionary age of their teens. In the 50s it could be a stamp collection that your dad bought from overseas after the war, that you cherished and admired. During the 60s and 70s it was vinyl discs from your favorite bands, while the 80s brought the love for comic books and cassettes in the scene. The grungy 90s fell for VHS tapes and the not so long ago 00s made us obsess over our alphabetically organized CD-ROM games.

Collections, in their most conventional sense, could be traced back in ancient times, with the Ptolemaic dynasty gathering thousands of books at the renowned Library of Alexandria, while the birth of the early bourgeois families in Renaissance Italy gave way to Europe’s first art collections. Moving on to the 18th century a quite peculiar system of collecting came to life. The so called cabinet of curiosities consisted of a wide range of artifacts, from prehistoric fossils, to gems, jewels from the „orient“ and taxidermy animals, all isolated from their original cultural context and historical connotations, just to be exhibited according to clear aesthetic principles.

The age of the revolutions argued for an open and public access to art and historical collections, from the 19th all the way to the very end of the 20th century, making the founding of Museum giants like the Louvre and the Hermitage the necessary next step. The Internet dominance and information culture of the 21st century brought in the forefront a series of critical questions around the theorization of various collecting processes. “The society of the spectacle” in which we live in favors a new intelligent mechanism of consumption that by extent provokes even more mass consumption. American television shows like Hoarders, where people with hoarding problems seek help for their addiction, illustrate the exact extent of collecting in the era of an unseen materialistic pluralism.

We collect driven by money, interest, memories, love, greed and curiosity. No matter what the motive may be the bottom line remains that very same powerful notion of narrative organization; the idea of telling a story, with a beginning, middle and an end (not necrssarily in that order). No matter how big or small, whether it’s like the ones you shout at the top of your lungs, or the ones you gently whisper in someone’s ear; the ones you secretly write down in a code with the hope they will never see the daylight, or those you yearn to accidently confess in front of your entire family during your cousins summer wedding.

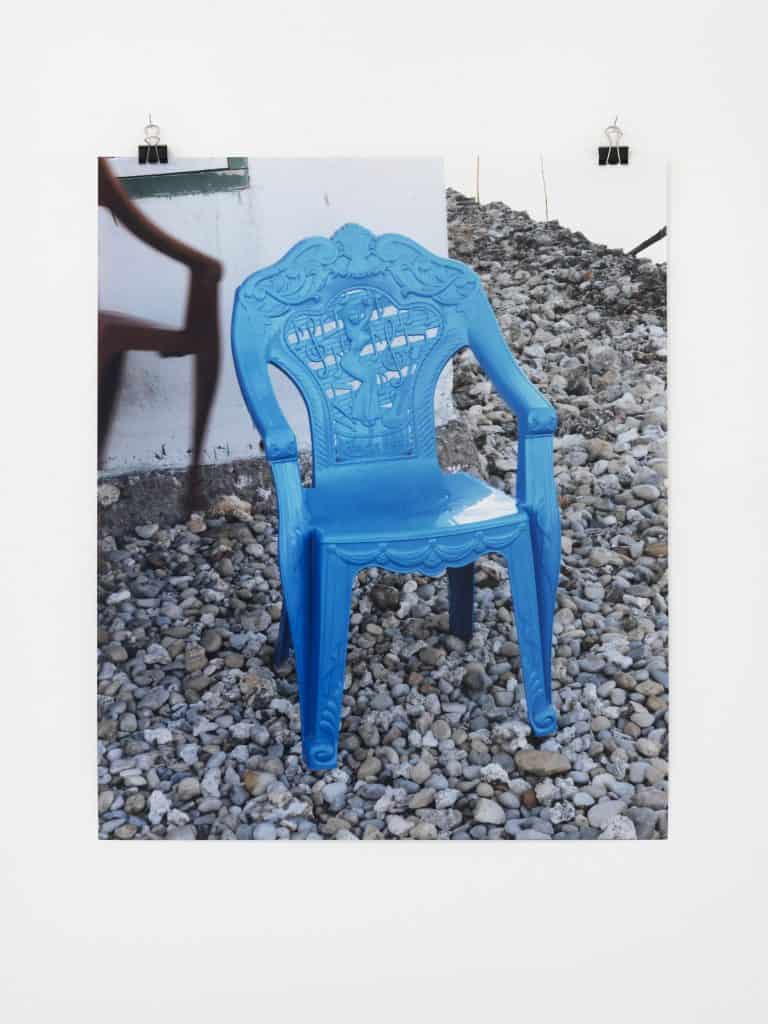

Oliver Husain | you are the gracious toe-twirled stumbler | 2016